Finger Lakes power plant at heart of crypto debate

A once coal-fired plant in rural, upstate New York stands at the center of a battle over Bitcoin. Greenidge Generation LLC mines “proof-of-work” cryptocurrency — the bitcoin cryptocurrency process requiring a massive amount of computing power. According to a Cambridge University analysis, globally, Bitcoin uses more electricity annually than the whole of Argentina.

For a small town in the Finger Lakes region, hosting Greenidge for bitcoin mining is seen as a blessing or a curse — an economic boon or an environmental danger.

Some see the plant as a test case for New York, particularly in economically challenged regions upstate. As the battle heats up, in late January the state Department of Environmental Conservation delayed a decision on whether to renew the plant’s air permit until March 31.

Why Greenidge?

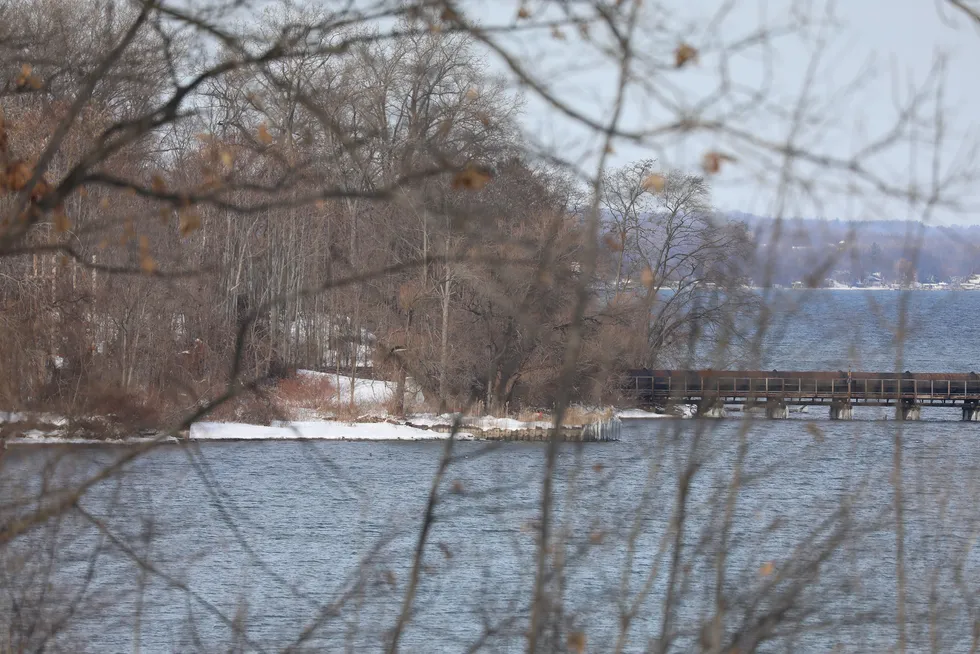

The plant outside the village of Dresden in the town of Torrey, Yates County, sits in New York’s Finger Lakes region of rolling hills, lakes, and vineyards. The factory stands out above the western shore of Seneca Lake, its red-brick smokestacks rising above the treetops.

Owned by private-equity firm Atlas Holdings, Greenidge converted a former coal-fired plant to natural gas and began producing electricity energy for the grid in 2017. In 2019, Greenidge started using the plant to power bitcoin mining to boost profits from surplus energy. (The company still supplies energy to the grid, including during a January cold snap when the company said it suspended mining to boost supply).

Hundreds of businesses and organizations are urging state lawmakers to put the brakes on Bitcoin — and specifically, to deny renewal of air permits Greenidge needs to continue operating. Greenidge also has strong supporters. They include town and county lawmakers, businesses and organizations that pinpoint economic benefits and believe the mining operation is safe.

Crypto 101:Here are 10 cryptocurrency terms people use every day from blockchain to NFT

More:Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are growing up and facing new scrutiny

A crypto crime crackdown?: DOJ hires first director of National Cryptocurrency Enforcement Team.

Steve Griffin, CEO of Finger Lakes Economic Development Center (Yates County’s sole economic development agency) said “Greenidge Generation continues to be a positive economic force in our community. They have created more technology-based jobs than they originally estimated at some of the highest paying salaries in the County.”

Cryptocurrency “is happening,” said Bina Ramamurthy, professor of Teaching in Computer Science and Engineering, University at Buffalo School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. She emphasized the process must be done in an environmentally sound way. She believes it can be, as long as plants like Greenidge are held accountable for following all rules and regulations.

The Greenidge plant has a capacity of 106 megawatts. Less than 50% of its capacity is used for Bitcoin mining and the remainder is on-demand at any time for the grid, according to Greenidge CEO Dale Irwin. In 2021, the plant mined 1,866 bitcoins. (Greenidge responded to questions for this story through an independent public relations company.)

Yet Bitcoin, the oldest form of cryptocurrency, is already being replaced by more sustainable forms of cryptocurrency. And that, say some, doesn’t bode well for Greenidge and other mining operations like it.

Bitcoin is “a bad model,” said Colin Read, professor of Economics and Finance at SUNY Plattsburgh. Read experienced some of the worst of what Bitcoin can do to a community after he was elected mayor of Plattsburgh in 2016. A crypto mining operation set up shop in Plattsburgh, a city of less than 20,000 that borders Canada. The miners came to take advantage of the cheap electricity there thanks to agreements over hydroelectric power from dams along the St. Lawrence River. The result: Residents saw a spike in electric rates, some as much as 40%.

What’s at stake

The state Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) says Greenidge has not demonstrated compliance with New York’s climate law that includes requirements regarding greenhouse gas emissions.

Greenidge refutes those claims, stating it is fully in compliance with current state and federal regulations. The company points to permits it was granted to operate the facility in Dresden and says it works with regulators to meet all requirements. It has also applied to expand its footprint to house additional computer servers.

Greenidge’s DEC water permit, which expires later this year, allows Greenidge to withdraw water from Seneca Lake for cooling the generator and return it to the Keuka Lake Outlet and eventually to Seneca Lake. Some are concerned the warmed water is contributing to blue-green algae blooms that threaten water quality and pose health risks. Opponents want the DEC to deny the air permit.

“We want the governor to act,” said Yvonne Taylor, co-founder and vice president of Seneca Lake Guardian, one of the organizations calling for a halt to Greenidge Bitcoin mining and a statewide moratorium on the process.

One of the latest events intended to bring pressure on lawmakers took place at Forge Cellars, a winery at the south end of Seneca Lake. At a press conference Jan. 31, Rick Rainey, Forge Cellars managing partner, pointed to the robust New York wine industry that generates over $6 billion annually, accounting for nearly 72,000 jobs and $2.8 in direct wages. “These are industries creating real things with real value — they are not speculative at their core. The costs are simply not worth the return,” said Rainey.

Kees Stapel, vineyard manager of Boundary Breaks Winery on Seneca Lake, asserted Greenidge is “using our environmental resources for their personal gains.” Stapel, an avid angler on the lake, said he has witnessed a decline in the fish population. He acknowledges a variety of factors can cause this, but he believes Greenidge pumping millions of gallons of warmed water daily to Seneca Lake is not helping matters.

A new Berkeley Haas working paper estimates that the power demands of cryptocurrency mining operations in upstate New York push up annual electric bills by about $165 million for small businesses and $79 million for individuals — with little or no local economic benefit.

“Small businesses operate on very thin margins, so I don’t think they’d be happy paying for the energy that cryptominers are using,” said Assistant Professor Matteo Benetton, who co-authored the paper with Associate Professor Adair Morse and Assistant Professor Giovanni Compiani, now at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business. “And the profits do not stay local: Bitcoin mining profits can be moved from upstate New York to Italy or Colombia or China in a second.”

“We cannot in good faith allow Greenridge’s subtle erosion of our natural resources to continue,” said Mark Pitifer, special projects manager for Waterloo Container, a supplier of wine bottles and other containers across the Finger Lakes region and East Coast.

Taylor, who spoke at rallies locally and in Albany, said she is heartened that DEC Commissioner Basil Seggos publicly stated his concerns. In a tweet Sept. 8, the commissioner said, “Greenidge has not shown compliance with NY’s climate law” based on goals in that law.

“New York state is leading on climate change,” Seggos said in a separate, prepared statement, “and we have some major concerns about the role cryptocurrency mining may play in generating additional greenhouse gas emissions.”

The Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA) signed into law in 2019, calls for reducing the release of greenhouse gasses 40% by 2030 and at least 85 percent by 2050 from 1990 levels. The state calls the Climate Act “among the most ambitious climate laws in the world,” to place New York on a path toward carbon neutrality.

Speaking at a Jan. 13, state Senate roundtable, Joseph Campbell, president of Seneca Lake Guardian, said “repowering or expanding coal and gas plants to make fake money in the middle of a climate crisis is literally insane.”

Dubbing the industry a “climate killer,” Campbell characterized bitcoin mining as “completely unregulated,” as “wealthy outside speculators are invading New York state to destroy our natural resources, kneecap local businesses, and keep us from meeting the crucial climate goals outlined by the CLCPA.”

Geneva City Councilman Ken Camera, who had a long career working with utility companies and as an energy consultant, said “there are bads and goods of power generation.” There are trade-offs, he said, but those “trade-offs must be acceptable for society.”

On its environmental impact, Read said Bitcoin generates more than a ton of carbon dioxide emissions for every transaction it processes. “This is vastly less efficient than, say, a credit card transaction.”

“There are far better alternatives that can inexpensively allow us to transact globally in seconds rather than hours, and at almost zero transaction costs. Our challenge is to figure out how to create a viable and properly regulated digital currency that is efficient and does not damage the environment.”

As more solar and wind come online with the state’s climate goals, Read sees that the Greenidge natural gas plant and those like it, fueling the energy-guzzling Bitcoin, will become more difficult to sustain.

Looking at the Greenidge model specifically, Read pointed out if Greenidge LLC, as Limited Liability Corporation, goes bankrupt, it would still be able to operate by taking all its assets and going elsewhere. That would leave the community burdened with a decommissioned plant.

He predicted the Bitcoin mining plant in Dresden won’t stick around. “They will be out of there in no time at all,” Read said.

Indeed, the Connecticut-based Greenidge has announced plans to expand its bitcoin mining operations outside of New York. The company announced in January that it was building a $264M data center near Spartanburg South Carolina, with the first phase opening later this year, the local NPR member station reported. The company said 40 permanent technology jobs would be created.

Wave of support

The Yates County Legislature last fall unanimously threw its support behind Greenidge, urging the DEC to renew the air permit. At a public hearing, Douglas Paddock, then chairman of the county legislature, testified the Greenidge plant had made a “significant contribution” to the area through tax payments and capital investments.

A county resolution cited Greenidge had created 45 high-paying jobs with an average wage in 2020 of $77,565 (well above the median household income in Yates County of $56,563, according to the latest U.S. Census figures). Tax payments to the town of Torrey, Penn Yan Central School, and Yates County had jumped by nearly $300,000, “due directly to the Greenidge data processing center,” according to the county, which anticipates further significant increases in future years.

County lawmakers cited a May 2021 economic impact study by Appleseed Inc. from the Greenidge website estimating the company’s combined operations and capital investments in 2020 directly and indirectly supported 108 jobs in the state with total earnings of nearly $8.4 million and nearly $16.8 million in statewide impact — “in 2020, during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, Greenidge supported over 80 businesses in NY,” according to the study.

In January, Greenidge announced the taxes it anticipates paying to the state of New York, Yates County, town of Torrey, and the Penn Yan Central School District for calendar-year 2021 will exceed $3 million – approximately $2 million higher than what the company paid just one year ago, in 2020.

Support for Greenidge comes from a number of businesses and organizations including O’Connell Electric, City Hill Construction, Hunt Engineers and the local 840 International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW), whose workers are partnering with Greenidge on site at the plant.

President Larry Lewis of Yates County Farm Bureau, an organization representing some 300 member families, issued a Farm Bureau statement of support. He said the organization “represents a broad base of the Yates County area community, which is heavily dependent on the agriculture and tourism economies.”

Local 840 of the IBEW, covering the Finger Lakes region, has about 175 members. At a public hearing, IBEW Local 840 Business Manager Mike Davis said, “While there has been a great deal of noise about Greenidge lately, there should be no ambiguity about where our loyalty falls at the IBEW; we stand with Greenidge because we know their record.”

According to Greenidge CEO Irwin, Greenidge is already a leader in environmental stewardship having eliminated coal and reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 70%. Irwin asserts Greenidge is “sending clean power to the Grid to support homes and businesses Upstate and operate a 100% fully carbon neutral bitcoin mining operation.”

Business fears

“Climate change is here, it’s documented, it’s evolving,” said Vinny Aliperti, a winemaker for more than 20 years. Aliperti and his wife Kim own Billsboro Winery on Seneca Lake. “I am pro-business, the wine industry is pro-business,” he said. When large companies buy up defunct power plants and run them 24/7, that concerns him.

Over the past few years what had been rare 15 years ago in his experience, is now more routine with warmer nights that top daytime temperatures. The trend has raised the incidence of crop disease and infections. “We are already under a lot of stress from climate change,” said Vinny, a member of Finger Lakes Wine Business Coalition, (FLWBC) one of the organizations urging the DEC to deny the Greenidge air permit and put a pause on bitcoin mining while the practice receives further scrutiny.

The FLWBC and like-minded groups believe increased air emissions to feed bitcoin mining and the millions of gallons a day of heated water going back into Seneca Lake can only be exacerbating climate change.

Greenidge says it’s in compliance with its permits and that the plant is 100% carbon neutral, thanks to the purchase of carbon offsets, such as forestry programs and projects that capture methane from landfills.

Commenting on Greenidge claims of “carbon neutral,” Read called this an example of “greenwashing” — making misleading claims about providing environmental benefits.

Read noted that to be truly carbon neutral, Greenidge would do what is called “carbon sequestration.” It would capture and store the atmospheric carbon dioxide it emits.

Ramamurthy pointed out that Bitcoin “is not a cottage industry,” existing only as a large-scale enterprise. Bitcoin is currently “like the wild west” — “it is new territory and over time it will settle down,” she said.

She said the efficiency of bitcoin mining is improving. Ramamurthy, director of UB’s Blockchain ThinkLab, mentioned a recent milestone — the first major upgrade for Bitcoin since 2017, which is expected to improve performance and make mining more efficient. “I am excited about it,” she said. How much it will improve performance, “we don’t know,” she added. “Everybody wants Bitcoin to improve.”

Water issues

In early October, Seneca Lake experienced a record-breaking Harmful Algal Bloom in the northwestern section of the lake, in the area of the Greenidge plant. There’s no evidence the mining operation contributed to the bloom. Other Finger Lakes including Canandaigua, Cayuga, and Keuka experienced blooms around the same time and multiple factors fuel HABs including wind and weather patterns.

“While it can’t be proved the plant is to blame, it is a concern,” said Taylor, adding the area of the lake around Dresden has been deemed a “hot spot” for HABs by the Seneca Lake Pure Waters Association, a nonprofit focused on preserving and protecting Seneca Lake.

Greenidge can discharge up to 134 million gallons of water into the Keuka Outlet (that eventually ends up back in Seneca Lake) every day, at a maximum temperature of 108 degrees Fahrenheit. (Four degrees hotter than the recommended safe maximum of 104 degrees for a hot tub.)

Additional issues have fueled opposition: The company has yet to install the required wedge wire screens that would protect fish and other aquatic life from being entrained and impinged.

According to Greenidge, the company has been working with the DEC to upgrade its cooling water intake system to meet modern standards for protecting fish and other aquatic life. The technology has to be specifically designed and engineered, according to Greenidge, and the company began a lengthy approval process for wedge wire screens after buying the facility in 2014. The DEC approved a pilot study for the system on August 7, 2020; approved a Technology Installation and Operation Plan on Dec. 22, 2020; and “has allowed Greenidge to move forward with final engineering, permitting, and construction of the approved screen system,” the company said.

The approved cylindrical wedge wire screens must be operational by Sept. 30, 2022, the expiration date of the facility’s current water permit. The company says “Greenidge is on schedule to meet this requirement.”

Sticking points

The DEC wrapped up public hearings and comment period on the air permit in November. The DEC stated it “has conducted a rigorous review of application materials and requested additional information.”

“Before making a final decision on the draft permits, DEC will thoroughly review all comments received and any additional information submitted by the applicant.”

The Climate Act is indeed a sticking point.

“Prior to issuing any permit for a proposed project, DEC needs to ensure compliance with the requirements of New York’s ambitious Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act,” DEC stated. “There are substantial greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with the project. Based on information currently available, the applicant has not demonstrated that the project is consistent with the attainment of statewide GHG emission limits established in the Climate Act, nor has the applicant provided a detailed justification notwithstanding this inconsistency or proposed sufficient alternatives or GHG mitigation measures.”

Greenidge maintains it operates entirely within its existing permits and is not seeking to expand power generation, stating: “Greenidge is not expanding power generation capacity at the Dresden facility, or anywhere else in the State of New York.”

Meanwhile, Seneca Lake Guardian, the Sierra Club and about 25 additional petitioners filed an Article 78 against the town of Torrey over its approval of a building expansion at the plant. The petition alleges the town failed to follow state Environmental Quality Review protocol in granting the expansion. Arguments were heard Feb. 16. by Yates County Supreme Court Judge Daniel Doyle.

The project involves four new buildings on the west side of the facility. Each of the single-story buildings would house computer servers. Greenidge maintains the additional space sought for computers does not affect energy use, as the plant is bound by its permitted 106 megawatt capacity.

“Noise is a constant and pressing concern,” said Ken Campbell, a Seneca Lake property owner about the expansion plan.

A view of the future

Professors Ramamurthy and Read agree cryptocurrency is the way of the future — and that it should, and can, be done right.

A new cryptocurrency method created in 2011, called “proof of stake,” validates transactions without mining, which requires a lot less energy consumption. Proof of stake “requires but a few well-protected machines,” said Read, as part of his testimony in January before Majority members of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce.

Ramamurthy cited considerations with Bitcoin mining. The computers run 24/7 and require the necessary hardware to do the job. The lifespan of these computers is much shorter than the lifespan of computers under normal usage. What happens to these mining computers at the end of their life? What happens to these racks and racks of high-power computers after their life is over? Can they be repurposed, not end up in landfills? These are questions Ramamurthy said must be answered.

Does she see plants like Greenidge in danger of leaving because Bitcoin will no longer be profitable? “The fear is always there for big companies, and sometimes they move,” she said. “Kodak moved.”

The professor sees benefit from cryptocurrencies, “bringing a lot of people together. There is engagement in this. We need to capture that,” she said.

Including reporting by USA Today, Associated Press, and The Chronicle Express

What is Bitcoin?

Bitcoin is not anything you can hold in your hand. It’s virtual money, a digital currency known as cryptocurrency that has been around since 2009. It is not tied to a bank or government. It allows users to spend money anonymously.

How does it work?

The currency uses a technology to facilitate instant payments and balances that are kept on a public ledger. The coins also can be bought and sold on exchanges with U.S. dollars and other currencies. You can use bitcoin just like traditional cash. Some businesses take bitcoin as payment, and a number of financial institutions allow it in their clients’ portfolios, though overall mainstream acceptance is still limited.

What is bitcoin mining?

Bitcoin mining is the method of verifying and processing bitcoin transactions. Mining uses sophisticated computing systems to create new bitcoins by solving complex puzzles. Bitcoin is a “proof-of-work cryptocurrency,” which needs an energy-intensive process running machines 24/7 to solve complex equations. Each machine requires energy to run, plus more energy to run cooling technology.